Resources

Virtual Treaty Day

Due to the continuing constraints and uncertainties brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Historical Society of Watertown will once again celebrate Treaty Day virtually in 2022. The HSW thanks you for participating and hopes that you find the information presented enlightening.

Hear ye! Hear ye! Pray give us your attention. Thank you friends, Watertownians, honored participants. The Historical Society of Watertown welcomes you to observe two important events that took place in July, 1776, at the Edmund Fowle House in Watertown, Massachusetts. On July 18, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read for the first time to the citizens of Watertown.

On July 19, 1776, the Treaty of Watertown was signed in the second floor room of the Edmund Fowle House that had been finished the year before as a meeting place for the Executive Council of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. This treaty was the first pact negotiated by the nascent United States of America with a foreign power, namely the St. John's (also called Maliseet) and Mi'kmaq Tribes of Nova Scotia.

The Mi'kmaq Gathering Song performed by Chief Jerome

The Edmund Fowle House was requisitioned in April, 1775, for the use of the Governor's Council, the executive branch, when the Massachusetts legislature convened here in Watertown during the first year and a half of the Revolutionary War. In an upstairs room at the Edmund Fowle House, the council and several committees carried on the day-to-day work of a civil government in time of war. A successor Governor's Council has continued to function to the present day.

Views of the Edmund Fowle House from pre-1896 (left) and circa 1900 (right)

The Fowle House in 1980 (left) and 2006 (right)

The newly-renovated Edmund Fowle House in 2008

A reading of the Treaty of Watertown by John Horrigan

Now let us return to the spring of 1776, here in Watertown, where the Council, the executive branch of the Massachusetts government was located. Some of the Councilors–John Hancock, John and Samuel Adams and Robert Treat Paine–had been sent to Philadelphia to represent Massachusetts in the Continental Congress. By spring of 1775, it was evident that Britain would not negotiate with the rebellious colonies. By June, when the Massachusetts House asked the towns what course they recommended, some two thirds of them had already considered the question, and all of them had voted for independence–most of them unanimously. As Joseph Hawley wrote from Watertown to Elbridge Gerry, "You cannot declare independence too soon."

In Philadelphia, meanwhile, Virginian Thomas Jefferson led a committee polishing the document that would formally sever allegiance to Great Britain. The blueprint for the Declaration of Independence, as determined by Harvard professor Danielle Allen, was John Adams's "Proclamation: The Frailty of Human Nature," presented to and approved by the Massachusetts legislature here in Watertown months before.

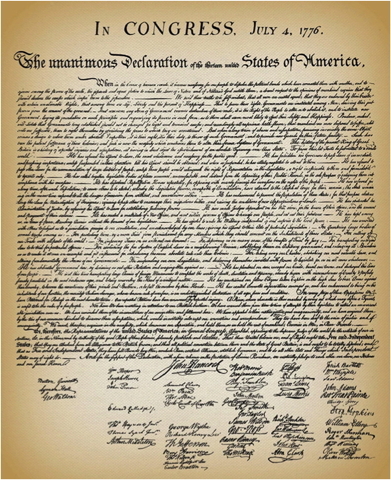

Congress then debated Jefferson's text for three days and approved it at last on July 4th. On that date, John Hancock, as President of the Continental Congress, signed his name–reputedly saying that he wrote it large enough for King George to read it without his spectacles. While the rest of the delegates signed the original, copies traveled to the governments of the thirteen colonies, now states, as fast as horse and man could carry them.

On July 16th, a copy reached the Watertown meeting house where the legislature was negotiating a treaty of alliance with delegates from the Mi'kmaq and St. John's (also called Maliseet) Indians of Nova Scotia. These ten delegates considered the significance of the document and were among the crowd of listeners on July 18th, when the Council Secretary, Perez Morton, proclaimed the Declaration of Independence to the whole town by reading it from a window of the Council Chamber at the Edmund Fowle House.

A reading of the Declaration of Independence by Max McLean

Among the throng of listeners that day were the delegates from several villages of the Mi'kmaq and St. John's tribes of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. In the months before, both the Council and General Washington had sent letters to these northern tribes urging them not to side with the British.

In the summer of 1776, Major Shaw journeyed with a delegation to Machias, Maine. From there, Major Shaw carried representatives of the tribes in his sloop to Salem, then accompanied them by carriage to Watertown, where they were welcomed in the Council Chamber on July 10th. Over the next few days, the delegations from both sides discussed an alliance.

James Bowdoin, as President of the Council, spoke for Massachusetts. Ambrose Bear (the clerk wrote the name as Var), Newell Wallis and Francis represented various villages of the St. John, the Maliseet of St. John's River. Joseph Denaquara, Charles, Mattahu Ontrane, Nicholas, John Battis, Peter, Andre and Sabbatis Netobcobwit represented the Mi'kmaq villages.

Ambrose Bear presented a sword, a pistol, and a silver gorget (a military officer's insignia) confiscated from a Mr. Anderson who had tried to persuade them to fight for the British. "[We] told him," said Bear, "we would have nothing to do with him, and...despised him. We told Anderson when we took the sword from him we would deliver it up to General Washington if he would receive it."

Video of a reenactment of the signing of the Treaty of Watertown

Henry Bear was our special guest at the annual Treaty Day celebration for the first time in July, 2014. He is a descendant of two of the signers of the Treaty of Watertown, Ambrose Bear and Newell Saulis (their names were recorded as Ambrose Var and Newell Wallis on the Treaty and in the minutes from 1776). Mr. Bear was also a member of the Maine House of Representatives, representing the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians from December 5, 2012, to December 4, 2018.

Representative Bear spoke about his ancestors who signed the Treaty of Waterown, gave some details about the men involved in the agreement and conveyed some of his thoughts about both. His remarks follow below.

Wuleewun and thank you, Marilynne, for your kind introduction. Greetings Elders, Chiefs, Representative and Honored Guests. I am Henry John Bear, a member of the St. John River Indians and present-day Maliseet Tribe. I am the elected Maliseet Tribal Representative to the Maine House of Representatives and a present-day relative of the late Maliseet Chief Ambrose Bear who was the lead spokesman during the July 10th through July 19th, 1776 treaty negotiation with the duly authorized representatives of the United States of America in this very place some 238 years ago today. I am also a present-day relative of Newall Saulis, another signer of that treaty. On behalf of my Tribe, I bring you greetings and will briefly share with you information about Maliseet Chief Ambrose Bear and our continuing Maliseet Tribal perspective with regard to this 1776 treaty with the United States of America.

But first, I want to mention that yesterday I had the privilege of holding the actual Watertown Treaty of 1776 in my hands, (Editor’s Note: located at the Massachusetts Archives in Dorchester) the original treaty signed by all of the Chiefs and headmen, and the Congressional Representatives and agents who were present here in Watertown at that time. When I placed my hand on the treaty at the very place it had been signed by Ambrose Bear a great pride swelled within me.

It was a reminder of the pride I feel whenever I observe the flag of the United States of America, the American flag, and the pride I feel whenever the Eagle Feather is brought forward before us in the tradition of my ancestors and elders. To me they are a continuing reminder that since the first days of this great American nation, beginning shortly after the signing of this first treaty here in Watertown, our respective peoples and warriors have honorably served and recognized each other’s sovereign interests as allies, as brothers, as equals.

That was what Maliseet Chief Bear set out to achieve as the lead spokesman for all of the eastern Indians. That is what Chief Bear was duly authorized to negotiate and conclude in this treaty, a treaty that he would successfully have ratified by an overwhelming majority of all the Maliseet Chiefs and people of the St. John River then, and still, centered in and around present day Meductic and Ecpahauq within our tribal homeland, which we have always called the Wuloostook, and what the United States calls the Aroostook region.

Chief Bear is believed to have lived to 1780 and was not a young man when he died. I understand that Ambrose had either observed, participated in or negotiated every treaty with the English and later, the British, including the treaties of 1725 and 26, 1749, 1760 and, finally, the Watertown Treaty of 1776 with British rebels turned “Americans”.

According to the historical record, it was Chief Ambrose Bear whom Colonel Jonathan Allen called upon to lead him and his colonial soldiers down the Maliseet Trail from the St. John River to Machias, which culminated in the successful Battle of Machias and defense of the entire northeast region from any further British attacks for the duration of the Revolutionary War.

It is important to note the fact that at the time of both the Declaration of Independence on July 4th through the 18th, 1776 and the signing of the Watertown Treaty of the same year, General George Washington, the Commanding General of the entire Continental Army could muster no more than 800 American soldiers at the time. On July 8th, 1776 only four days after signing the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress resolved to authorize General Washington to secure the Treaty. On July 11th he wrote back stating he had written the General Court of Massachusetts Bay and that he desired five or six hundred of the Eastern Indians to be enlisted for two or three years.

Thus the 600 tribal members to be raised according to the treaty terms negotiated by James Bowdoin and Chief Ambrose Bear, was a result of George Washington’s express desire. His plan was to add 250 white soldiers to that number in order to form the whole regiment under American officers, which would have provided a significant advantage for General Washington.

And when, in 90 canoes with a force of more than 480 Indians, Maliseet Chief Bear and my other treaty relative and treaty signer, Newell Saulis, kept our tribe’s promises, in good faith, under the express terms of the Watertown Treaty, and they did so believing that this treaty was binding on both the Maliseet Tribe and the United States of America, a treaty that has never been expressly abrogated or terminated by the Maliseet or the United States and is, therefore, still in force and relied upon to this day.

To be clear, this Declaration of Independence and this Watertown Treaty of a few days later was not understood by the United States or by Maliseet Chief Ambrose Bear to be temporary, but instead was and still is, understood to have a continuing existence, at least with respect to the principles of freedom and equality in the Declaration, and with respect to the mutual pledges of aid and assistance, mutual pledges of respecting each other’s sovereignty and jurisdictions, mutual pledges guaranteeing trade and exclusive Maliseet tribal access to tribal land and natural resources that such trade relied upon contained in the Treaty. In fact, United States citizens who were trespassing, it was agreed, were to be removed from Maliseet tribal lands in the Maine district and, as Congressional records indicate, trading posts or truck houses at both Machias and Old Town were furnished and funded by the United States Congress for nearly half a century after the conclusion of the American’s War for Independence.

It is clear in the minutes of the treaty negotiations that this was the perspective of Chief Ambrose Bear and the other tribal delegates who signed the treaty at the time, and it is still the perspective of the Maliseet Tribe today. And that perspective, to be clear, is that the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America and its companion document, the Watertown treaty of 1776 both continue in effect and both certainly deserve to be honored to this day.

In concluding my remarks I want to express my appreciation for having been allowed to participate as a duly elected and appointed Representative of the Maliseet Tribe. I would urge each of us to ensure our respective governments and Peoples continue to honor this Treaty, to hold to its promises, its duties and its obligations so that we can mutually and separately continue to share in its benefits - that of alliance, that of friendship, that of trade for necessaries and conveniences, and for a continuing relationship as co-equals, as brothers, one brother not subservient nor superior to the other, just as both General Washington clearly stated in his letters and just as the negotiators and signers indicated in the plain language of this Treaty.

To that end, this celebration is both appropriate and necessary to ensure that this message is passed on to our respective children and grandchildren, that there still exists such a unique, one-of-a-kind treaty-based relationship between our Maliseet Tribe and the people of the United States of America and that, because of this Treaty, it can contribute to there being an even better and more secure tomorrow for them.

In my tribal homeland there now exists and Aroostook Treaty Education Center that, like your Historical Society of Watertown, seeks to inform and educate about this Declaration of Independence and this Treaty to ensure that as we move further into the 21st century and this new millennium, we do so by reminding ourselves and others of our historic alliance, that our respective national stories are married at the hip, and that we, the Maliseet People, are your first and oldest partners in this continuing and wonderful American adventure, an adventure that still requires we adhere to the principles and promises contained in your Declaration of Independence and our July 19, 1776 Treaty.

Wuleewun and thank you for hearing me today.

Native American representatives in attendance at a Treaty Day celebration,

including Barbara Casey (far left), United Native American Cultural Center

Chief Roland Jerome (far right) and Noel Rainville (facing Chief Jerome)

The Historical Society of Watertown's virtual celebration of Treaty Day 2021 honored the memory of our dear friend and colleague, Chief Roland Jerome of the United Native American Cultural Center (UNACC) in Devens, MA. Chief Jerome was raised and educated in Gesgapegiag First Nation, Quebec, Canada, located on the south shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. He was proud of his Mi'kmaq ancestry and shared his knowledge with us. We will always be grateful to Chief Jerome for his dedication to the Society's annual Treaty Day event, his leadership and his friendship. Rest in Peace, Chief Jerome.

Chief Roland Jerome, Aug 5, 1943 - Jan 24, 2020

The Historical Society of Watertown thanks you for your interest in the history of our town and its significance to our country's history. Please browse our entire web site for more information about the HSW, its mission and philosophy, membership, future programs and tours or to make a donation.