The Edmund Fowle House During the Revolutionary War

A study of historic records and the existing building fabric began this summer and is still in progress at this time. Architectural Conservators, including a nationally renowned conservator of early American structures and a preservation carpenter, all engaged by McGinley Kalsow, have been looking under floor boards, baseboards, existing woodwork and wallpaper to see what lurks beneath. They will analyze different plasters, lathe characteristics, nails and paint samples to try to unravel the timeline of changes made to this historic structure.

A professional researcher has also been engaged and has turned up some fascinating documents and historic facts linked to the start of the Revolutionary War and the role of the Edmund Fowle House during that time.

We are quite certain that these studies will reveal where the Council Chamber was located when the Executive Council of the Second and Third Provincial Congress met here in 1775-1776. These studies will also help us to better understand the changes made to the house during its long history.

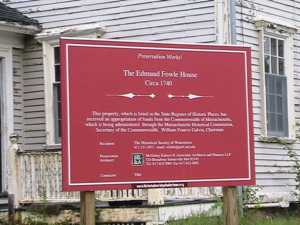

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Preservation Works! project sign

The bright red “Preservation Works” sign has been put up in front of the house. This sign is required by the MHC for all state-funded projects while work is being done at the site. It identifies the Edmund Fowle House as being on the State Register of Historic Places and states that the Historical Society of Watertown has received an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that is being administered through the MHC.

The Fowle House played an important role in the founding of our government and country. A room on the second floor was used as the meeting place for the Executive Council and the Clerks’ office as well as for meetings for various committees in 1775-1776.

Following the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773 the British Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts in March 1774 which, among other things, closed the Port of Boston until the city had paid for the tea which had been thrown into the harbor. The charter of the colony was also annulled. This eliminated their right to assemble and self govern, outlawed the Massachusetts Legislature, and imposed governing directly from England. This outraged the colonists. Several towns began stockpiling munitions.

General Gage, the British Military Governor, summoned the Massachusetts Assembly to meet in Salem on October 5, 1774 to legislate under the new ruling of Parliament. Alarmed by the single-mindedness and determination displayed by the colonists and their preparations for defense, General Gage felt it might be risky to allow the Assembly to meet so he issued a decree dismissing the assembly members from attendance. The colonists refused to be denied their right to meet at this time and ninety of the delegates assembled in Salem at the time appointed in spite of the dismissal and organized themselves into a Provincial Congress, including several sub-committees such as the Committee of Safety, the Committee of Correspondence and the Committee of Supplies, to consider what was necessary for the safety and defense of the Colony. With John Hancock as president this renegade body operated as the Government of all of Massachusetts outside British controlled Boston and began meeting in Concord and in Cambridge. The towns continued to purchase and store ammunition.

The Provincial Congress met on April 11, 1775 in Concord, a safe distance from the British occupied Boston. On April 18 British forces were sent to Concord to destroy the colonists’ military supplies. The following day the battles in Lexington and Concord occurred thus marking the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

On April 22, 1775 the Provincial Congress adjourned to the Watertown Meetinghouse, located in the Common Street Cemetery. (Today, four granite posts with plaques mark the four corners of the meetinghouse that stood there from 1755 to 1836.) Military preparations dominated their working hours. Many new Committees were formed to help with these preparations.

On May 24, John Hancock was elected President of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia and beloved local physician and patriot Dr. Joseph Warren took over as President of the Provincial Congress. Dr. Warren was killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.

By now, many patriots had fled Boston to seek refuge in safer places. Watertown had many taverns and inns, being a crossroad over the Charles River, and was a popular place for the refugees to stay. According to Maud Hodges in Crossroads on the Charles, “In 1775 there were approximately 100 dwellings with an average of seven persons living in each, hence room could be made for newcomers.”

On July 2, 1775 General George Washington arrived in Watertown on his way to take command of the troops in Cambridge. He stopped first to eat at the Coolidge Tavern, which was located at the present site of the carbarn where Galen Street meets the Charles River in Watertown Square. (A granite marker with a metal plate marks this place today.) He then proceeded to the Meetinghouse where he was greeted enthusiastically by the cheers of the townspeople as the Commander of the Continental Army.

On July 19, the Third Provincial Congress dissolved. The next day, after having elected representatives from the towns, James Warren, then President of the Congress, was elected Speaker of the House of Representatives. An Executive Council of 28 members was also elected on July 20. These two bodies proceeded to govern the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Members of the Executive Council included John Hancock, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine, Moses Gill, Benjamin Lincoln, James Bowdoin and others.

A July 22, 1775 entry in the Journals of the House of Representatives states “The Committee appointed to provide some convenient Place for the Council to sit in; reported, verbally, That a large Chamber in the House of Mr. Fowle’s might be procured; but being unfinished, the Committee recommended that there be a rough Floor laid, and Chairs provided for that Purpose. The Report was accepted, and Capt. Brown, Capt. Dix, and Major Fuller, were appointed to prepare said Chamber accordingly.”

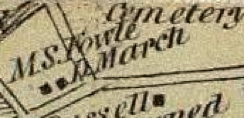

1852 map showing the original location of the Edmund Fowle House

and its proximity to the Meetinghouse on Common Street Cemetery

At this time the Edmund Fowle House was at its original location on Mount Auburn Street, then called Mill Street. It would remain there for another century. (The 1852 map above shows the house in its original location, before it was moved to the newly cut Marshall Street, when it was owned by Marshall Spring Fowle [1788-1855], the son of Edmund and the last descendant to live in it. The Delano March house, also shown in the 1852 map below, was not there.) Its close proximity to the Common Street Cemetery where the Meetinghouse was located (approx where the word “Fowle” is on the map), made it a desirable location for the Executive Council meetings.

As mentioned earlier in this article, McGinley Kalsow & Associates, our architectural firm, has engaged the services of a professional researcher – Ric Detwiller of New England Landmarks. He has turned up some fascinating facts, including a bill for “18 Chairs and one Great Chair from John and Thomas Larkin of Charlestown” on June 17, 1775 to the Province of Massachusetts Bay. These were apparently ordered for the Committee of Safety but were burned in a warehouse fire during the Battle of Bunker Hill. One other interesting note about this item is that John Larkin is the Deacon Larkin that loaned the horse to Paul Revere for his ride on April 18.

Several other invoices were uncovered including two from David Bemis of Watertown on July 28, 1775 for “three large tables and a desk for the Council Chamber” and a “Chest and Lock for the Use of the Committee”. Various orders for carpentry work, tools and building materials were found as well as bills from Uriah Norcross, David Parker and others to the Colony of Massachusetts for “work done at the Council Chamber”.

On July 27, James Warren was also elected as the Continental Army Paymaster. By this time, Paul Revere had fled Boston and was living with his wife and six of his children at the John Cooke House in Watertown near the site of what is now the intersection of Watertown and California Streets. (There is a granite headstone marking this site today.) Here he printed the Colonial Notes to pay the expenses of the war effort. Also living at the Cooke House was printer Benjamin Edes who published the June 5, 1775 edition of the Boston Gazette in that house and later editions in a Watertown shop.

A sketch of the Watertown Meetinghouse

drawn by architecht Charles Brigham

In October 1775 Edmund Fowle and Dorothy Coolidge, owner of the Coolidge Tavern were paid a sum of money for “preparing the entertainment for the Gentlemen from ye Several Colonies… per order of the Commee of the House of Reps…” Members of the House met in the Coolidge Tavern while the Meetinghouse was being outfitted with a stove and other things for them. Another bill located by Mr. Detwiller dated December 10, 1775 speaks of “making 2 Elbows to the funnell [i.e. stove pipe] for the Meeting House, working 12 plates of tin for a funnell for ye Meeting House...”

James Warren, as Speaker of the House of Representatives, spent much time in the Fowle House conducting business and slept here when he was in town, which was often. He wrote to John Adams from here on October 20, 1775 saying, “After an interval much longer than I ever designed should take place, I now sit down to write again. The multiplicity of business, and the crowd of company here, must be my excuse. Every body either eats, drinks or sleeps in this house, and very many do all, so that for a week past I could get no opportunity to write, morning, noon, or night.”

On January 9, 1776 an entry from the Journals of the House of Representatives states that Edmund Fowle was to be paid “out of the Treasury of this Colony, the Sum of Four Pounds Ten Shillings, for the extraordinary Trouble that Committees have occasioned in sitting in his House from the first Day of the Congress sitting in this Town to this Day, and for Expence of Wood and Candles, and Damage done his Furniture.”

The Historical Society of Watertown celebrates the Treaty of Watertown every July with a weekend colonial encampment and Native American Pow Wow. This treaty of alliance and friendship with the Mic Maq and St. John’s Indians was signed in the Fowle House in the Council Chamber on July 19, 1776 and deliberations leading to the signing were held in the Meetinghouse. This was the first international treaty signed by the newly formed United States of American a mere 15 days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Entries from the Journals of the House of Representatives on July 10, 1776 read, “…informed the House, that ten Chiefs of the Michmack and St. John’s tribe of Indians, were arrived in town…”, on July 11 read, “that the honorable Board proposed that a conference should be held with the Indian Chiefs, now in Watertown, before both Houses, tomorrow morning, at ten o’clock, and that the conference be held in the meeting-house…”, and on July 12, 1776 read, “The House, having assigned two pews for the honorable Council, for their seats, during the conference with the Indians, and having also allotted seats for the Indians. The Treaty itself reads, “…Delegates of the St. John’s Tribes…, Delegates of the Mickmac Tribes who hereunto put their Marks, and Seals in the Council Chamber at Watertown in the State aforesaid the Nineteenth day July in the year of our Lord One thousand and seven Hundred, and seventy-six.”

These are just some of the highlights of known historic facts and some newly discovered ones. Much more information is available already and more is being uncovered by way of our architectural firm. We will report more in our next newsletter.

McGinley, Kalsow & Assoc.are also studying the building itself. The wall between the two rooms on the second floor on the right of the house has been taken down by Robert Adams and his students from the North Bennett Street School, a prestigious trade school for artisans in the North End. Their objective was to carefully dismantle new fabric saving old fabric. We know this wall was not originally there because part of the fireplace in the front of the room was located in the closet The removal of this wall exposed unseen finishes and edges.

The back wall adjacent to the bathroom is also not an original wall. Of course, the bathroom is not original, either. Much of the original structure has been uncovered, including some wood portions that have never even had paint on them. The plaster expert engaged by our architects, Andy Ladygo, has discovered that many of the plaster ceilings are original plaster from the 1700s including the large room and bathroom mentioned above and a front room on the first floor.

Bathroom and large room on the second floor with the wall removed

The ceiling in the room with the bay window has been taken down. This has exposed original hand-hewn beams as well as 19th-20th century wooden 2X4s that must have been put up during a renovation of that room.

The ceiling in the first floor room with the bow window was removed,

revealing old, wide, wooden planks and modern 2x4s

An overall physical needs assessment has been done to help us determine what must be done to make the building compliant to the Mass. State Building Code and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Plans have been drawn up for presentation.